By Wg Cdr Arun Singh(Retd)

Golf began in the Eastern Scotland few centuries ago and the game was played with primitive equipment in the earliest days. The oldest reference to the golf clubs being specially made comes from the year 1502 when King James IV of Scotland commissioned a Bow maker to make a set of clubs for him. In the early days, the set of clubs consisted of ‘Longnoses’ for driving, ‘Grass Drivers’ for fairways, ‘spoons’ for short range shots, ‘Niblicks’ for pitching and a ‘Putting Cleek’ for putting. Introduction of ’Featherie’ golf ball standardised one aspect of the equipment and the clubs started getting standardised too.

The early standard for making golf clubs was the use of hard wood (holly, beech, pear, and apple) for the head and softer wood (Ash, Hazel) for the shaft. The Head and Shaft were connected with a splint and tightly bound with leather straps. The whole process was expensive and time consuming so the cost of these clubs could not be afforded by common people. It was common for an odd club to break while playing a round which added to the costs and the game became elitist.

A club maker in Scotland began importing Hickory from USA for the shafts in early 19th century and the introduction of ‘Guttie’ ball few years later necessitated the change in the design of ‘Longspoons’ into ‘Bulgers’ with bulbous heads similar to what we see today.

Well known Scottish Professionals like Alan Robertson, Old Tom Morris and Willie Park Sr ran a thriving industry of manufacturing clubs and balls in their Pro Shops and then exporting it to golfers all over the world. Golfers around the world associated Scotland with golf and the business was very lucrative. By 1900 ‘Persimmon’ imported from the USA had replaced hard wood like Bleech and experimentation with Aluminium had also begun.

Advent of Drop Forging had already encouraged the use of Iron in the manufacturing of golf club heads and it was common to see hickory shaft clubs with iron heads. Creating steel shafts for golf clubs was still a difficult proposition because of the weight. Blacksmiths such as Thomas Horsburgh started experimenting with Steel shafts in the late 1890s but the adoption was very slow. Thomas Horsburgh was bullish on the prospects of steel shafts and obtained a patent in 1893. The solid steel made the shafts very heavy and the clubs did not gain any popularity which resulted in the patent being allowed to lapse by the owner.

Failure with solid steel shafts due to its weight led to experimentation with steel tubes. This again proved to be a tough proposition because techniques to manufacture steel tubes wasn’t easily available in those days and the tubes were prone to extensive breakages during the manufacturing process. Meanwhile, with the advancement of steel making technologies in USA, lot of effort to find new solutions shifted there. In 1910 Arthur (Bill) F Knight, a former engineer with General Electric, was granted a patent for steel shafts. His clubs also failed to gain traction among general public mainly because both R&A and USGA refused to accord sanction on the grounds of steel shafts being ‘artificial assistance’! Arthur Knight was unable to develop a marketable steel shaft and in 1920 Horton Manufacturing Company bought the patent on royalty basis as the patent still had seven more years to run.

Meanwhile, in 1915, Alan Lard of Washington was granted a patent for perforated steel shafts. Alan Lard made his shafts from solid steel having six sides and bored hundreds of small holes to reduce the weight. These shafts when swung, made a strong whistling sound and picked up the nickname of ‘whistler’. The perforations on ‘whistler’ increased the club head speed considerably and reduced torque but the clubs failed to gain popularity.

Meanwhile, in 1915, Alan Lard of Washington was granted a patent for perforated steel shafts. Alan Lard made his shafts from solid steel having six sides and bored hundreds of small holes to reduce the weight. These shafts when swung, made a strong whistling sound and picked up the nickname of ‘whistler’. The perforations on ‘whistler’ increased the club head speed considerably and reduced torque but the clubs failed to gain popularity.

Horton Company continued on the path of trying to manufacture a steel shaft. Apart from paying royalty to Arthur Knight, they also paid royalty to General Electric for using their processes of Brazing. They made hundreds of experiments to fold thin steel strips into tapered tubes by using hydrogen brazing, heat treatment etc. Everything from size, weight distribution an entirely new process and the first set of production shafts was ready by June 1921. They got immediate commercial success and found Crawford, Mcgregor and Candy Company as their first customer. Soon after, Spalding, who were experimenting with Alan Ward’s perforated shafts, also became a client. Sale of steel shafts began in earnest in 1922 and Horton Company was surely on a roll or was it too soon to celebrate?!

Horton Company got a shocking setback when in 1923, USGA barred the shafts from official play on the grounds of it being a mechanical aid! The steel shaft clubs were not to be used in USGA sanctioned championships until it could be proved to be not a mechanical aid and its use will not provide any undue advantage. Fortunately for Horton Company, the provincial associations were well organised and effective bodies in USA (unlike our situation). The company got in touch with Western Golf Association who organised testing at Edgewater Golf Club in Chicago. Horton Company went on record to show their appreciation for the officials of the Association and the club for their friendliness and cooperation but were effusive in praise for their attitude to help the game.

Many golf Pros were initially opposed to the steel shafted clubs in the beginning because of their apprehension of it impacting their club making business but soon realised that it actually helped. Horton Company, in the meantime announced that they would gift a steel shaft club to anyone registering a hole in one provided they submitted an attested score card. To their surprise, they received 700 applications and honoured their promise. The company then requested all the recipients of the steel shaft clubs to write to USGA to give an honest opinion about the clubs and more than 600 recipients obliged. USGA too was surprised with the letters and wrote to Horton Company to inquire about the kind of influence they had used!

The efforts of Horton Company and help from Western Golf Association backed by so many users seems to have worked and steel shafts in golf clubs were approved by USGA in early 1924. Herbert Lagerblade, a professional player who had been helping Horton Company with the development and promotion of ‘Bristol’ steel shafts, became the first player to swing a steel shaft golf club in the US National Championship in the same year at Oakland Hills Golf Club. He called his drive as ‘the shot which was heard around the world’ primarily because a lot of future of the shafts depended on it. Winner of the US Open that year, Cyril Walker also used steel shaft on his putter. It was not surprising that steel rapidly grew in popularity and soon overtook wood.

In 1929 True Temper developed the first seamless, step down tapered shaft which allowed them to decrease the outside diameter in a tapering fashion to fit into the head. This helped them to create different flexes to cater to individual needs. Then in 1930, Spalding unveiled their Bobby Jones signature steel shaft clubs which were painted brown to give it a hickory look. The practice was adopted by others to make the transition from hickory to steel easier. Very soon in 1931, Billy Burke became the first to win US championship by using the entire set of steel shaft golf clubs. The transition was complete.

Even after the approval of USGA in early 1924. The challenge still loomed across the continent because the R&A refused to approve the steel shaft clubs. Steel shafts were initially banned by the R&A in 1914 on the grounds of being ‘’not permissible departure from the traditional form and make of golf clubs’’. We must appreciate that Rules on Clubs did not exist before 1908 and R&A was only beginning to come to grips with them in those early years. In the beginning, ban on steel shafts seemed logical as with little technological innovations, standardisation was difficult. Horton Company (later Bristol Steel) creating a seamless shaft overcame the obstacle and USGA allowed it’s use in 1924 onward after it was demonstrated that it gave no unfair advantage to a player.

Even after the approval of USGA in early 1924. The challenge still loomed across the continent because the R&A refused to approve the steel shaft clubs. Steel shafts were initially banned by the R&A in 1914 on the grounds of being ‘’not permissible departure from the traditional form and make of golf clubs’’. We must appreciate that Rules on Clubs did not exist before 1908 and R&A was only beginning to come to grips with them in those early years. In the beginning, ban on steel shafts seemed logical as with little technological innovations, standardisation was difficult. Horton Company (later Bristol Steel) creating a seamless shaft overcame the obstacle and USGA allowed it’s use in 1924 onward after it was demonstrated that it gave no unfair advantage to a player.

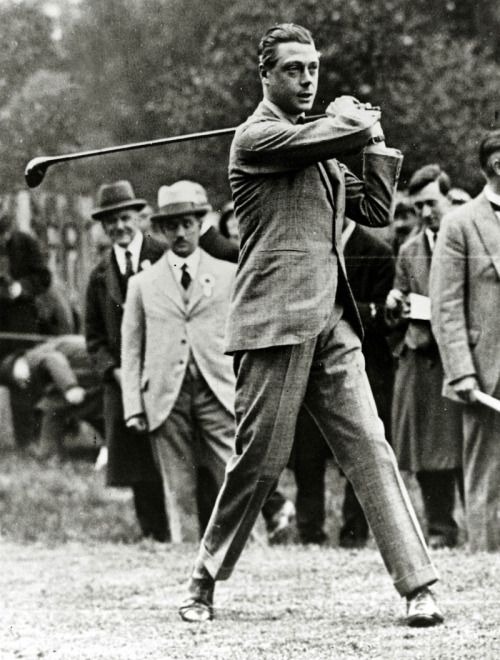

R&A continued with its opposition to the steel shafts in order to be ‘’ repelling novelties that seek to cross the Atlantic’’! The approval was doggedly resisted despite increasing public pressure as these clubs were long lasting and provided better value for money. Fortunately, a fortuitous royal intervention took place through the Prince of Wales in 1929.

In September 1922, Prince of Wales (later to be King Edward VIII and Duke of Windsor after abdication) was invited to be the Captain of R&A. He was a keen golfer who patronised St Andrews and liked travelling to USA often, partly because of its attractiveness as a golfing destination. The Prince acquired a set of steel shaft clubs during one his visits to USA and liked them. R&A, in the meantime, was sticking to its position of not allowing the steel shaft golf clubs in its jurisdiction.

The Prince of Wales arrived to play an event in the Old Course in 1929 and strode in with his set of steel shaft clubs acquired in the USA. He played his round, submitted his card and left. The committee at R&A was caught in a fix because as per rules the player must be penalised with ‘Disqualification’ for playing with a set of unauthorised equipment. It was something which would have been hugely embarrassing as the player was a former Captain of the R&A and the future monarch of the country. The committee met quickly and legalised the play by steel shaft golf clubs based on the USGA’s findings!

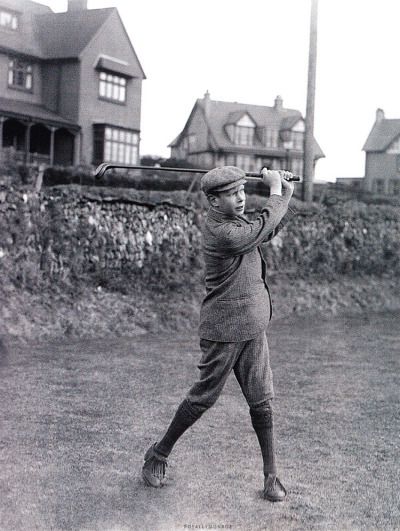

Steel shafts were thus approved by the R&A and it was befitting that Prince Albert, the younger brother of Prince of Wales, who was Duke of York then, was invited to be the Captain of R&A in 1930. He arrived for the ceremonial tee off and became the first Captain to tee off with a set of steel shaft golf club. Prince Albert was to later succeed Edward VIII, after his abdication, as George VI the King of England. The Royal intervention had certainly helped the steel shaft golf clubs.